Spartacus (film)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Spartacus | |

|---|---|

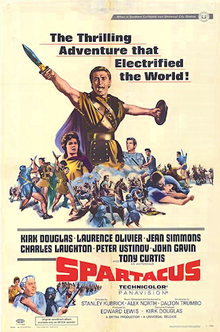

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown

| |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick Anthony Mann (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Edward LewisKirk Douglas (executive) |

| Screenplay by | Dalton Trumbo |

| Based on | Spartacus by Howard Fast |

| Narrated by | Vic Perrin |

| Starring | Kirk Douglas Laurence Olivier Jean Simmons Charles Laughton Peter Ustinov John Gavin Tony Curtis |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Editing by | Robert Lawrence |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

| Release date(s) |

|

| Running time | 184 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million |

| Box office | $60,000,000 |

The film stars Kirk Douglas as rebellious slave Spartacus and Laurence Olivier as his foe, the Roman general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus. Co-starring are Peter Ustinov (who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role as slave trader Lentulus Batiatus), John Gavin (as Julius Caesar), Jean Simmons, and Charles Laughton. The film won four Oscars in all.

Anthony Mann, the film's original director, was replaced by Douglas with Kubrick after the first week of shooting. [1] It is the only film directed by Kubrick where he did not have complete artistic control.

Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was blacklisted at the time as one of the Hollywood Ten. Kirk Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus, and President John F. Kennedy crossed picket lines to see the movie, helping to end blacklisting.[2][3] The author of the novel on which it is based, Howard Fast, was also blacklisted, and originally had to self-publish it.

The film became the biggest moneymaker in Universal Studios' history, until it was surpassed by Airport (1970).[4]

Contents

[hide]Plot[edit source | edit]

In the 1st century BC, the Roman Republic has slid into corruption, its menial work done by armies of slaves. One of these, a proud and gifted man named Spartacus, is so uncooperative in his servitude that he is sentenced to fight as a gladiator. He is trained at a school run by the unctuous Roman businessman Lentulus Batiatus, who instructs Spartacus's trainer Marcellus to bully the slave mercilessly and break his spirit. Amid the abuse, Spartacus forms a quiet relationship with a serving woman named Varinia, whom he refuses to rape when she is sent to "entertain" him in his cell.Batiatus receives a visit from the Roman senator Marcus Licinius Crassus, an arch-conservative who aims to become dictator of Rome. Crassus buys Varinia on a whim, and for the amusement of his companions arranges for Spartacus and three others to fight in pairs. When Spartacus is disarmed, his opponent, an African named Draba, spares his life in a burst of compassion and attacks the Roman audience. Crassus kills Draba. The next day, with the school's atmosphere still tense over this episode, Batiatus takes Varinia away to Crassus' house in Rome. Spartacus kills Marcellus, who was taunting him over this, and their fight escalates into a riot. The gladiators overwhelm their guards and escape into the Italian countryside.

Spartacus is elected chief of the fugitives and decides to lead them out of Italy and back to their homes. They plunder Roman country estates as they go, collecting enough money to buy sea transport from Rome's foes the pirates of Cilicia. Countless other slaves join the group, making it as large as an army. One of the new arrivals is Varinia, who escaped while being delivered to Crassus. Another is a slave entertainer named Antoninus, who also fled Crassus' service after the Roman tried to seduce him. Privately Spartacus feels mentally inadequate because of his lack of education during years of servitude. However, he proves an excellent leader and organizes his diverse followers into a tough and self-sufficient community. Varinia, now his informal wife, becomes pregnant by him, and he also comes to regard the spirited Antoninus as a sort of son.

The Roman Senate becomes increasingly alarmed as Spartacus defeats the multiple armies it sends against him. Crassus' populist opponent Gracchus knows that his rival will try to use the crisis as a justification for seizing control of the Roman army. To try and prevent this, Gracchus channels as much military power as possible into the hands of his own protege, a young senator named Julius Caesar. Although Caesar lacks Crassus' contempt for the lower classes of Rome, he mistakes the man's rigid outlook for nobility. Thus, when Gracchus reveals that he has bribed the Cilicians to get Spartacus out of Italy and rid Rome of the slave army, Caesar regards such tactics as beneath him and goes over to Crassus.

Crassus uses a bribe of his own to make the pirates abandon Spartacus and has the Roman army secretly force the rebels away from the coastline towards Rome. Amid panic that Spartacus means to sack the city, the Senate gives Crassus absolute power. Now surrounded by Romans, Spartacus convinces his men to die fighting. Just by rebelling, and proving themselves human, he says, they have struck a blow against slavery. In the ensuing battle, most of the slave army is massacred by Crassus' forces. Afterward, when the Romans try to locate the rebel leader for special punishment, every surviving man shields him by shouting "I'm Spartacus!"

Meanwhile, Crassus has found Varinia and Spartacus' newborn son and has taken them prisoner. He is disturbed by the idea that Spartacus can command more love and loyalty than he can and hopes to compensate by making Varinia as devoted to him as she was to her former husband. When she rejects him, he furiously seeks out Spartacus (whom he recognizes from having watched him in the arena) and forces him to fight Antoninus to the death. The survivor is to be crucified, along with all the other men captured after the great battle. Spartacus kills Antoninus to spare him this fate. The incident leaves Crassus worried about Spartacus' potential to live in legend as a martyr. In other matters he is also worried about Caesar, who he senses will someday eclipse him.

Gracchus, having seen Rome fall into tyranny, commits suicide. Before doing so, he bribes his friend Batiatus to rescue Spartacus' family from Crassus and carry them away to freedom. On the way out of Rome, the group pass under Spartacus' cross. Varinia is able to comfort him in his dying moments by showing him his little son, who will grow up without ever having been a slave.

Cast[edit source | edit]

- Kirk Douglas as Spartacus

- Laurence Olivier as Crassus

- Jean Simmons as Varinia

- Charles Laughton as Gracchus

- Peter Ustinov as Batiatus

- Tony Curtis as Antoninus

- John Gavin as Julius Caesar

- John Dall as Marcus Glabrus

- Nina Foch as Helena Glabrus

- John Ireland as Crixus

- Herbert Lom as Tigranes Levantus (pirate envoy)

- Charles McGraw as Marcellus

- Woody Strode as Draba

Production[edit source | edit]

The development of Spartacus was partly instigated by Kirk Douglas's failure to win the title role in William Wyler's Ben-Hur. Douglas had worked with Wyler before on Detective Story, and was disappointed when Wyler chose Charlton Heston instead. Shortly after, Edward (Eddie) Lewis, a vice-president in Douglas's production company, Bryna (named after Douglas's mother), had Douglas read Howard Fast's novel, Spartacus, which had a related theme—an individual who challenges the might of the Roman Empire—and Douglas was impressed enough to purchase an option on the book from Fast with his own financing. Universal Studios eventually agreed to finance the film after Douglas persuaded Olivier, Laughton and Ustinov to act in it. Lewis became the producer of the film, with Douglas taking executive producer credit. Lewis went on to produce several more films for Douglas.[1]Screenplay development[edit source | edit]

Originally, Howard Fast was hired to adapt his own novel as a screenplay, but he had difficulty working in the format. He was replaced by Dalton Trumbo, who had been blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten. He used the pseudonym "Sam Jackson".Kirk Douglas insisted that Trumbo be given screen credit for his work, which helped to break the blacklist.[5] Trumbo had been jailed for contempt of Congress in 1950, after which he had been surviving by writing screenplays under assumed names. Douglas' intervention on his behalf was praised as an act of courage.

In his autobiography, Douglas states that this decision was motivated by a meeting that he, Edward Lewis and Kubrick had regarding whose name/s to put against the screenplay in the movie credits, given Trumbo's shaky position with Hollywood executives. One idea was to credit Lewis as co-writer or sole writer, but Lewis vetoed both suggestions. Kubrick then suggested that his own name be used. Douglas and Lewis found Kubrick's eagerness to take credit for Trumbo's work revolting, and the next day, Douglas called the gate at Universal saying, "I'd like to leave a pass for Dalton Trumbo." Douglas writes, "For the first time in ten years, [Trumbo] walked on to a studio lot. He said, 'Thanks, Kirk, for giving me back my name.'"[1]

The filming was plagued by the conflicting visions of Kubrick and Trumbo. Kubrick complained that the character of Spartacus had no faults or quirks, and he later distanced himself from the film.[6] Despite the on-set troubles, Spartacus's critical and commercial success established Kubrick as a major director.

Blacklisting effectively ended in 1960 when it lost credibility. Trumbo was publicly given credit for two blockbuster films: Otto Preminger made public that Trumbo wrote the screenplay for the smash hit, Exodus,[7] and Kirk Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus.[8] Further, President John F. Kennedy crossed picket lines to see the movie.[2][3]

Filming[edit source | edit]

Thirty-year-old Stanley Kubrick was hired to take over. He had already directed four feature films (including Paths of Glory, also starring Douglas). Spartacus was a bigger project by far, with a budget of $12 million and a cast of 10,500, a daunting project for such a young director (although his contract did not give him complete control over the filming). Cinematographer Russell Metty complained about Kubrick's unusually precise and detailed instructions for the film's camerawork. But Metty remained on the production and later won the Oscar for Best Cinematography, Color for the film.

Spartacus was filmed using the 35 mm Technirama format and then blown up to 70 mm film. This was a change for Kubrick, who preferred using square-format ratios. Kubrick found working outdoors or in real locations to be distracting and thus preferred to film in the studio. He believed the actors would benefit more from working on a sound stage, where they could fully concentrate. To create the illusion of the large crowds that play such an essential role in the film, Kubrick's crew used three-channel sound equipment to record 76,000 spectators at a Michigan State – Notre Dame college football game shouting "Hail, Crassus!" and "I'm Spartacus!"

The intimate scenes were filmed in Hollywood, but Kubrick insisted that all battle scenes be filmed on a vast plain outside Madrid. Eight thousand trained soldiers from the Spanish infantry were used to double as the Roman army. Kubrick directed the armies from the top of specially constructed towers. However, he eventually had to cut all but one of the gory battle scenes, due to negative audience reactions at preview screenings.

Music[edit source | edit]

| This section possibly contains original research. (November 2009) |

The soundtrack album runs less than forty-five minutes and is not very representative of the score. There were plans to re-record a significant amount of the music with North's friend and fellow film composer Jerry Goldsmith, but the project kept getting delayed. Goldsmith died in 2004. Numerous bootleg recordings have been made, but none has good sound quality.

In 2010 the soundtrack was re-released as part of a set, featuring 6 CDs, 1 DVD, and a 168-page booklet. This is a limited edition of 5,000 copies.[9]

Political commentary, Christianity, and reception[edit source | edit]

The film parallels 1950s American history with the McCarthy Hearings as well as the civil rights movement. The McCarthy Hearings, which demanded witnesses to "name names" of supposed communist sympathizers, closely resembles the final scene when the slaves, asked by Crassus to give up their leader by pointing him out from the multitude, each stand up to proclaim, "I am Spartacus". Howard Fast, who wrote the book on which the film was based, "was jailed for his refusal to testify, and wrote the novel Spartacus while in prison.”[10] The comment of how slavery was a central part of American history is pointed to in the beginning in the scenes featuring Draba and Spartacus. Draba, who denies the friendship of Spartacus claiming "gladiators can have no friends", sacrifices himself by attacking Crassus rather than kill Spartacus. This scene points to the fact that Americans are indebted to the suffering of African Americans who played a major role in building the country. The fight to end segregation and to promote the equality of African Americans is seen in the mixing of races within the gladiator school as well as in the army of Spartacus where all fight for freedom.[11] Another instance of the film's allusions to the political climate of the United States is hinted at in the beginning where Rome is described as a republic "that lay fatally stricken with a disease called human slavery," and describing Spartacus as a "proud, rebellious son dreaming of the death of slavery, 2000 years before it finally would die"; thus the ethical and political vision of the film is first introduced as a foreground for the ensuing action.[12]The voice-over at the beginning of the film also depicts Rome as destined to fail by the rise of Christianity: "In the last century before the birth of the new faith called Christianity which was destined to overthrow the pagan tyranny of Rome and bring about a new society, the Roman Republic stood at the very centre of the civilised world . . . Even at the zenith of her pride and power, the Republic lay fatally stricken with the disease called human slavery. The age of the dictator was at hand, waiting in the shadows for the event to bring forth. In that same century, in the conquered Greek province of Thrace, an illiterate slave woman added to her master's wealth by giving birth to a son whom she names Spartacus. A proud rebellious son, who was sold to living death in the mines of Libya, before his thirteenth birthday. There under whip and chain and sun he lived out his youth and his young manhood, dreaming the death of slavery 2000 years before it finally would die."

Thus Rome is portrayed as the oppressor suffering from its own excesses, where the prospect of Christian salvation is offered as the means to end Roman oppression and slavery. [13]

The film's release occasioned both applause from the mainstream media and protests from anti-communist groups such as the National Legion of Decency who picketed theaters showcasing the film. To affirm the film's "legitimacy as an expression of national aspirations wasn’t stilled until the newly elected John F. Kennedy crossed a picket line set up by anti-communist organizers to attend the film”.[10]

Re-releases and restoration[edit source | edit]

The film was re-released in 1967 (in a version 23 minutes shorter than the original release), and again in 1991 with the same 23 minutes restored by Robert A. Harris, plus an additional 14 minutes that had been cut from the film before its original release. This addition includes several violent battle sequences. It also has a bath scene in which the Roman patrician and general Crassus (Olivier) attempts to seduce his slave Antoninus (Curtis), speaking about the analogy of "eating oysters" and "eating snails" to express his opinion that sexual preference is a matter of taste rather than morality.When the film was restored (two years after Olivier's death), the original dialogue recording of this scene was missing; it had to be re-dubbed. Tony Curtis, by then 66, was able to re-record his part, but Crassus' voice was an impersonation of Olivier by the actor Anthony Hopkins. A talented mimic, he had been a protege of Olivier during his days as the National Theatre's Artistic Director and knew his voice well.

Some four minutes of the film are lost, because of Universal's mishandling of its film prints in the 1970s. These scenes relate to the character of Gracchus (Laughton), including a scene where he commits suicide. The audio tracks of these scenes have survived. They are included on the Criterion Collection DVD, alongside production stills of some of the lost footage.

Awards and nominations[edit source | edit]

Academy Awards[edit source | edit]

Spartacus has been on 5 different AFI 100 Years... lists including #62 for thrills, #22 for heroes, #44 for cheers and #81 for overall movies.In June 2008, AFI revealed its "10 Top 10"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Spartacus was acknowledged as the fifth best film in the epic genre.[14][15]

- American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated[16]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #62

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Spartacus – #22 Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "I'm Spartacus! I'm Spartacus!" – Nominated[17]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #81

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – #5 Epic film

Critical reception[edit source | edit]

The movie received mixed reviews when first released, but over time its reputation has gained in stature. Critics such as Roger Ebert have argued that the film has flaws, though his review is generally positive otherwise.[18] When released, the movie was attacked by both the American Legion and the Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper because of its connection with Trumbo. Hopper stated, "The story was sold to Universal from a book written by a commie and the screen script was written by a commie, so don't go to see it."[1]Bosley Crowther called it a "spotty, uneven drama."[19] It has a 96% (fresh) rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[20]

"I'm Spartacus!"[edit source | edit]

In the climactic scene, recaptured slaves are asked to identify Spartacus in exchange for leniency; instead, each slave proclaims himself to be Spartacus, thus sharing his fate. The documentary Trumbo[5][verification needed] suggests that this scene was meant to dramatize the solidarity of those accused of being Communist sympathizers during the McCarthy Era who refused to implicate others, and thus were blacklisted.Regarding this scene, an in-joke is used in Kubrick's next film, Lolita (1962), where Humbert Humbert asks Clare Quilty, "Are you Quilty?" to which he replies, "No, I'm Spartacus. Have you come to free the slaves or something?"[21] Many subsequent films, television shows and advertisements have referenced or parodied the iconic scene. One of the most notable is the 1979 film Monty Python's Life of Brian, which reverses the situation by depicting an entire group undergoing crucifixion all claiming to be Brian, who, it has just been announced, is eligible for release ("I'm Brian"; "No, I'm Brian"; "I'm Brian and so's my wife.")[21] Further examples have been documented[21] in David Hughes' The Complete Kubrick[22] and Jon Solomon's The Ancient World in Cinema.[23]

See also[edit source | edit]

References[edit source | edit]

- ^ a b c d Kirk Douglas. The Ragman's Son (Autobiography). Pocket Books, 1990. Chapter 26: The Wars of Spartacus.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Richard A. "How the Film and Television Blacklists Worked". Florida International University. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Kennedy Attends Movie in Capital". New York Times. 1961-02-04. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Link, Tom (1991). Universal City-North Hollywood: A Centennial Portrait. Chatsworth, CA: Windsor Publications. p. 87. ISBN 0-89781-393-6.

- ^ a b Trumbo (2007) at the Internet Movie Database Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ Winkler, Martin M. Spartacus: Film and History, p. 4. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 1-4051-3181-0

- ^ Nordheimer, Jon (September 11, 1976). "Dalton Trumbo, Film Writer, Dies; Oscar Winner Had Been Blacklisted". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved 2008-08-11. "... it was Otto Preminger, the director, who broke the blacklist months later by publicly announcing that he had hired Mr. Trumbo to do the screenplay ..."

- ^ Harvey, Steve (September 10, 1976). "Dalton Trumbo Dies at 70, One of the 'Hollywood 10'". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. "He recalled how his name returned to the screen in 1960 with the help of Spartacus star Kirk Douglas: 'I had been working on Spartacus for about a year ..."

- ^ Varèse Sarabande Records: "Varèse Sarabande Records" 11 October 2010

- ^ a b Burgoyne, Robert. The Hollywood Historical Film, p. 93. Blackwell, 2008. ISBN 1-4051-4603-6

- ^ Burgoyne, Robert. The Hollywood Historical Film, pp. 86-90. Blackwell, 2008. ISBN 1-4051-4603-6

- ^ Burgoyne, Robert. The Hollywood Historical Film, p. 73. Blackwell, 2008. ISBN 1-4051-4603-6

- ^ Theodorakopoulos, Elena. Ancient Rome at the Cinema: Story and Spectacle in Hollywood and Rome, pp. 54-55. Bristol Phoenix, 2010. ISBN 978-1-904675-28-0

- ^ American Film Institute (2008-06-17). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ "Top 10 Epic". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees

- ^ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes Nominees

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1991-05-03). "Spartacus". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (1960-10-07). "'Spartacus' Enters the Arena:3-Hour Production Has Premiere at DeMille". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ "Spartacus Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ a b c Winkler, Martin M. Spartacus: Film and History, pp. 6-7, fn. 12. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 1-4051-3181-0

- ^ Hughes, David. The Complete Kubrick. London: Virgin, 2000; rpt. 2001, pp. 80-82. ISBN 0-7535-0452-9

- ^ Solomon, Jon. The Ancient World in Cinema, 2nd edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001, p. 53. ISBN 0-300-08337-8

External links[edit source | edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Spartacus (film) |

- Spartacus at the Internet Movie Database

- Spartacus at Rotten Tomatoes

- Criterion Collection essay by Stephen Farber

- Rare, Never-Seen: 'Spartacus' at 50 at LIFE

| |||

| ||

| ||

Categories:

- 1960 films

- English-language films

- 1960s drama films

- American films

- American drama films

- Films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- Screenplays by Dalton Trumbo

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Bisexuality-related films

- Epic films

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winning performance

- Films set in ancient Rome

- Films set in Capua

- Films set in Rome

- Films shot in Madrid

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films set in the 1st century BC

- Universal Pictures films

- Third Servile War films

- Spartacus

- Films about rebels

- Historical fiction

Thus Rome is portrayed as the oppressor suffering from its own excesses, where the prospect of Christian salvation is offered as the means to end Roman oppression and slavery.

ReplyDeleteI don't believe Christian 'salvation' which does not exist to me is 'offered as a means to end' Roman oppression or slavery. Christianity does not condemn slavery in it's religious text. I don't believe Christianity ended Roman oppression but helped contribute to it.