Themes in Avatar

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

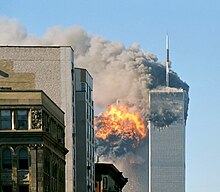

Discussion has centered around such themes as the conflict between modern man and nature, and the film's treatment of imperialism, racism, militarism and patriotism, corporate greed, property rights, spirituality and religion. Commentators have debated whether the film's treatment of the human aggression against the native Na'vi is a message of support for indigenous peoples today, or is, instead, a tired retelling of the racist myth of the noble savage.[8][9] Right-wing critics accused Cameron of pushing an "anti-American" message in the film's depiction of a private military contractor that used ex-Marines to attack the natives, while Cameron and others argued that it is pro-American to question the propriety of the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The visual similarity between the destruction of the World Trade Center and the felling of Home Tree in the film caused some filmgoers to further identify with the Na'vi and to identify the human military contractors as terrorists. Critics asked whether this comparison was intended to encourage audiences to empathize with the position of Muslims under military occupation today.[10][11]

Much discussion has concerned the film's treatment of environmental protection and the parallels to, for example, the destruction of rainforests, mountaintop removal for mining and evictions from homes for development. The title of the film and various visual and story elements provoked discussion of the film's use of the iconography of Hinduism, which Cameron confirmed had inspired him.[12][13] Christians, including the Vatican, worried that the film promotes pantheism over Christian beliefs, while others instead thought that it sympathetically explores biblical concepts. Other critics either praised the film's spiritual elements or found them hackneyed.[14]

Contents

[hide]Political themes

Imperialism

Avatar describes the battle by an indigenous people, the Na'vi of Pandora, against the oppression of alien humans. Director James Cameron acknowledged that the film is "certainly about imperialism in the sense that the way human history has always worked is that people with more military or technological might tend to supplant or destroy people who are weaker, usually for their resources."[8] Critics agreed that the film is "a clear message about dominant, aggressive cultures subjugating a native population in a quest for resources or riches."[15] George Monbiot, writing in The Guardian, asserted that conservative criticism of Avatar is a reaction to what he called the film's "chilling metaphor" for the European "genocides in the Americas", which "massively enriched" Europe.[16] Cameron told National Public Radio that references to the colonial period are in the film "by design".[17] Adam Cohen of The New York Times compared the struggle of the Na'vi with "a 22nd-century version of the American colonists vs. the British, India vs. the British Raj, or Latin America vs. United Fruit."[18]

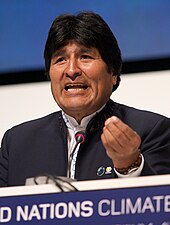

Bolivian President Evo Morales praised Avatar for "resistance to capitalism" and the "defense of nature".[19]

Many commentators saw the film as a message of support for the struggles of native peoples today. Evo Morales, the first indigenous president of Bolivia, praised Avatar for its "profound show of resistance to capitalism and the struggle for the defense of nature".[19] Others compared the human invaders with "NATO in Iraq or Israel in Palestine",[10] and considered it reassuring that "when the Na'vi clans are united, and a sincere prayer is offered, the ... 'primitive savages' win the war."[23] Palestinian activists painted themselves blue and dressed like the Na'vi during their weekly protest in the village of Bilin against Israel's separation barrier.[24][25] Other Arab writers, however, noted that "for Palestinians, Avatar is rather a reaffirmation and confirmation of the claims about their incapability to lead themselves and build their own future."[26] On the other hand, Forbes columnist Reihan Salam criticized the vilification of capitalism in the film, asserting that it represents a more noble and heroic way of life than that led by the Na'vi, because it "give[s] everyone an opportunity to learn, discover, and explore, and to change the world around us."[27]

Militarism

Cameron stated that Avatar is "very much a political film" and added: "This movie reflects that we are living through war. There are boots on the ground, troops who I personally believe were sent there under false pretenses, so I hope this will be part of opening our eyes."[28] He confirmed that "the Iraq stuff and the Vietnam stuff is there by design",[17] adding that he did not think that the film was anti-military.[29] Critic Charles Marowitz in Swans magazine remarked, however, that the realism of the suggested parallel with wars in Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan "doesn't quite jell" because the natives are "peace-loving and empathetic".[30]Cameron argued that Americans have a "moral responsibility" to understand the impact of their country's recent military campaigns. Commenting on the term "shock and awe" in the film, Cameron said: "We know what it feels like to launch the missiles. We don't know what it feels like for them to land on our home soil, not in America."[31] Christian Hamaker of Crosswalk.com noted that, "in describing the military assault on Pandora, Cameron cribs terminology from the ongoing war on terrorism and puts it in the mouths of the film's villains ... as they 'fight terror with terror'. Cameron's sympathies, and the movie's, clearly are with the Na'vi—and against the military and corporate men."[32] A columnist in the Russian newspaper Vedomosti traced Avatar's popularity to its giving the audience a chance to make a moral choice between good and evil and, by emotionally siding with Jake's treason, to relieve "us the scoundrels" of our collective guilt for the cruel and unjust world that we have created.[33][34] Armond White of New York Press dismissed the film as "essentially a sentimental cartoon with a pacifist, naturalist message" that uses villainous Americans to misrepresent the facts of the military, capitalism, and imperialism.[35] Answering critiques of the film as insulting to the U.S. military, a piece in the Los Angeles Times asserted that "if any U.S. forces that ever existed were being insulted, it was the ones who fought under George Armstrong Custer, not David Petraeus or Stanley McChrystal."[7] Other reviews saw Avatar as "the bubbling up of our military subconscious ... the wish to be free of all the paperwork and risk aversion of the modern Army—much more fun to fly, unarmored, on a winged beast."[36]

A critic writing in Le Monde opined that, contrary to the perceived pacifism of Avatar, the film justifies war in the response to attack by the film's positive characters, particularly the American hero who encourages the Na'vi to "follow him into battle. ... Every war, even those that seem the most insane [are justified as being] for the 'right reasons'."[11] Ann Marlowe of Forbes saw the film as both pro- and anti-military, "a metaphor for the networked military".[36]

Anti-Americanism

Cameron argued that "the film is definitely not anti-American"[44] and that "part of being an American is having the freedom to have dissenting ideas."[28] A critic for MTV concurred that "it'd take a great leap of logic to tag 'Avatar' as anti-American or anti-capitalist."[45] Ann Marlowe called the film "the most neo-con movie ever made" for its "deeply conservative, pro-American message".[36] But Cameron admitted to some ambiguity on the issue, agreeing that "the bad guys could be America in this movie, or the good guys could be America in this movie, depending on your perspective",[8] and stated that Avatar's defeat at the Academy Awards might have been due to the perceived anti-U.S. theme in it.[29]

The destruction of the Na'vi habitat Hometree reminded commentators of the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center,[36] one calling it a "tacky metaphor"[41] and others criticizing Cameron for his "audacious willingness to question the sacred trauma of 9/11".[35][46] Cameron said that he was "surprised at how much it did look like September 11", but added that he did not think that it was necessarily a bad thing.[31] A French critic wrote: "How can one not see the analogy with the collapse of the towers of the World Trade Center? Then, after that spectacular scene, all is justified [for the unified] indigenous peoples (the allied forces) ... to kill those who [are] just like terrorists."[11] Another writer noted that "the U.S.' stand-ins are the perpetrators, and not the victims" and described this reversal as "the movie’s most seditious act".[46]

Social and cultural themes

Civilization and race

Commentators around the world sought to interpret the relationship between the Na'vi and humans in the film, mostly agreeing with Maxim Osipov, who wrote in the Hindustan Times and The Sydney Morning Herald: "The 'civilised humans' turn out as primitive, jaded and increasingly greedy, cynical, and brutal—traits only amplified by their machinery—while the 'monkey aliens' emerge as noble, kind, wise, sensitive and humane. We, along with the Avatar hero, are now faced with an uncomfortable yet irresistible choice between the two races and the two worldviews." Osipov wrote that it was inevitable that the audience, like the film's hero, Jake, would find that the Na'vi's culture was really the more civilized of the two, exemplifying "the qualities of kindness, gratitude, regard for the elder, self-sacrifice, respect for all life and ultimately humble dependence on a higher intelligence behind nature."[47][48] Echoing this analysis, psychologist Jeffery Fine in The Miami Herald urged "every man, woman and child" to see the film and wake up to its message by making the right choice between commercial materialism, which is "steamrolling our soul and consciousness", and reconnection with all life as "the only ... promise of survival" for humanity.[49] Similarly, an Angolan critic saw the film as a message of hope, writing, "With this union of humans and aliens comes a feeling that something better exists in the universe: the respect for life."[50] Cameron confirmed that "the Na'vi represent the better aspects of human nature, and the human characters in the film demonstrate the more venal aspects of human nature."[28]Conversely, David Brooks of The New York Times opined that Avatar creates "a sort of two-edged cultural imperialism", an offensive cultural stereotype that white people are rationalist and technocratic while colonial victims are spiritual and athletic and that illiteracy is the path to grace.[21] A review in the Irish Independent found the film to contrast a "mix of New Age environmentalism and the myth of the Noble Savage" with the corruption of the "civilized" white man.[51] Reihan Salam, writing in Forbes, viewed it as ironic that "Cameron has made a dazzling, gorgeous indictment of the kind of society that produces James Camerons."[27]

Māori academic Rawiri Taonui agreed that the film portrays indigenous people as being simplistic and unable to defend themselves without the help from "the white guys and the neo-liberals."[56] Another author remarked that while the white man will fix the destruction, he will never feel guilty, even though he is directly responsible for the destruction."[26] Likewise, Josef Joffe, publisher-editor of Die Zeit in Germany, said the film perpetuates the myth of the "noble savage" and has "a condescending, yes, even racist message. Cameron bows to the noble savages. However, he reduces them to dependents."[57] Slavoj Žižek argued that "the film enables us to practise a typical ideological division: sympathising with the idealised aborigines while rejecting their actual struggle."[58] The Irish Times carried the comment that "despite all the thematic elements from Hinduism, one thing truly original is the good old American ego. Given its Hollywood origins, the script has remained faithful to the inherent superiority complex, and has predictably bestowed the honor of the 'avatar' not on the movie’s native Na’vis, but on a white American marine."[59] Similarly, positing that "the only good humans [in the film] are dead—or rather, resurrected as 'good Navi'", a writer in The Jerusalem Post thought that the film was inadvertently promoting supremacy of one race over another.[60]

On the Charlie Rose talk show, Cameron acknowledged parallels with idea of the "noble savage", but argued: "When indigenous populations who are at a bow and arrow level are met with technological superior forces, [if] somebody doesn't help them, they lose. So we are not talking about a racial group within an existing population fighting for their rights."[3] Cameron rejected claims that the film is racist, asserting that Avatar is about respecting others' differences.[52] Adam Cohen of The New York Times felt similarly, writing that the Na'vi greeting "I see you" contrasts with the oppression of, and even genocide against, those who we fail to accept for what they are, citing Jewish ghettos and the Soviet gulags as examples.[18]

Environment and property

Avatar has been called "without a doubt the most epic piece of environmental advocacy ever captured on celluloid.... The film hits all the important environmental talking-points—virgin rain forests threatened by wanton exploitation, indigenous peoples who have much to teach the developed world, a planet which functions as a collective, interconnected Gaia-istic organism, and evil corporate interests that are trying to destroy it all."[61] Cameron has spoken extensively with the media about the film's environmental message, saying that he envisioned Avatar as a broader metaphor of how we treat the natural world.[9][62][63] He said that he created Pandora as "a fictionalised fantasy version of what our world was like, before we started to pave it and build malls, and shopping centers. So it's really an evocation of the world we used to have."[64] He told Charlie Rose that "we are going to go through a lot of pain and heartache if we don't acknowledge our stewardship responsibilities to nature."[3] Interviewed by Terry Gross of National Public Radio, he called Avatar a satire on the sense of human entitlement: "[Avatar] is saying our attitude about indigenous people and our entitlement about what is rightfully theirs is the same sense of entitlement that lets us bulldoze a forest and not blink an eye. It's just human nature that if we can take it, we will. And sometimes we do it in a very naked and imperialistic way, and other times we do it in a very sophisticated way with lots of rationalization—but it's basically the same thing. A sense of entitlement. And we can't just go on in this unsustainable way, just taking what we want and not giving back."[17] An article in the Belgium paper De Standaard agreed: "It's about the brutality of man, who shamelessly takes what isn't his."[65]Commentators connected the film's story to the endangerment of biodiversity in the Amazon rainforests of Brazil by dam construction, logging, mining, and clearing for agriculture.[66] A Newsweek piece commented on the destruction of Home Tree as resembling the rampant tree-felling in Tibet,[67] while another article compared the film's depiction of destructive corporate mining for unobtanium in the Na'vi lands with the mining and milling of uranium near the Navajo reservation in New Mexico.[68] Other critics, however, dismissed Avatar's pro-environmental stance as inconsistent. Armond White remarked that, "Cameron’s really into the powie-zowie factor: destructive combat and the deployment of technological force. ... Cameron fashionably denounces the same economic and military system that make his technological extravaganza possible. It’s like condemning NASA—yet joyriding on the Mars Exploration Rover."[35] Another author called the film "socialism-disguised-as-nonsense enviro stuff" and argued that the very process of creation and promotion of Avatar emitted enough carbon to undermine the film's ecological message.[69] Similarly, an article in National Review concluded that by resorting to technology for educating viewers of the technology endangered world of Pandora, the film "showcases the contradictions of organic liberalism."[63]

Stating that such conservative criticism of his film's "strong environmental anti-war themes" was not unexpected, Cameron stressed that he was "interested in saving the world that my children are going to inhabit",[70] encouraged everyone to be a "tree hugger",[28] and urged that we "make a fairly rapid transition to alternate energy."[71] The film and Cameron's environmental activism caught the attention of the 8,000-strong Dongria Kondh tribe from Orissa, eastern India. They appealed to him to help them stop a mining company from opening a bauxite open-cast mine, on their sacred Niyamgiri mountain, in an advertisement in Variety that read: "Avatar is fantasy ... and real. The Dongria Kondh ... are struggling to defend their land against a mining company hell-bent on destroying their sacred mountain. Please help...."[72][73] Similarly, a coalition of over fifty environmental and aboriginal organizations of Canada ran a full-page ad in the special Oscar edition of Variety likening their fight against Canada's Alberta oilsands to the Na'vi insurgence,[74] —a comparison the mining and oil companies objected to.[75][76] Cameron was awarded the inaugural Temecula Environment Award for Outstanding Social Responsibility in Media by three environmentalist groups for portrayal of environmental struggles that they compared with their own.[77]

The destruction of the Na'vi habitat to make way for mining operations has also evoked parallels with the oppressive policies of some states often involving forcible evictions related to development. David Boaz of the libertarian Cato Institute wrote in Los Angeles Times that the film's essential conflict is a battle over property rights, "the foundation of the free market and indeed of civilization."[78] Melinda Liu found this storyline reminiscent of the policies of the authorities in China, where 30 million citizens have been evicted in the course of a three-decade long development boom.[67][79] An article in the Global Times, published by the Chinese Communist Party's official newspaper People's Daily, called the film's plot "the spitting image of the violent demolition in our everyday life. ... [F]acing the violent demolition conducted by chengguan but instigated by real estate developers, some ordinary people have wept or burned themselves desperately, while most continue to bear unfairness in silence."[80] Others saw similar links to the displacement of tribes in the Amazon basin[66] and the forcible demolition of private houses in a Moscow suburb.[81]

Religion and spirituality

Avatar comes from a childhood sense of wonder about nature... You fly in your dreams as a child, but you tend not to fly in your dreams as an adult. In the Avatar state, [Jake] is getting to return to that childlike dream state of doing amazing things.

James Cameron[17]

James Cameron has said that he "tried to make a film that would touch people's spirituality across the broad spectrum."[64] He also stated that one of the film's philosophical underpinnings is that "the Na'vi represent that sort of aspirational part of ourselves that wants to be better, that wants to respect nature, while the humans in the film represent the more venal versions of ourselves, the banality of evil that comes with corporate decisions that are made out of remove of the consequences."[17][28][44] Film director John Boorman saw a similar dichotomy as a key factor contributing to its success: "Perhaps the key is the marine in the wheelchair. He is disabled, but Mr Cameron and technology can transport him into the body of a beautiful, athletic, sexual, being. After all, we are all disabled in one way or another; inadequate, old, broken, earthbound. Pandora is a kind of heaven where we can be resurrected and connected instead of disconnected and alone."[51]

Religions and mythology

Reviewers suggested that the film draws upon many existing religious and mythological motifs. Vern Barnet of the Charlotte Observer opined that Avatar poses a great question of faith—should the creation be seen and governed hierarchically, from above, or ecologically, through mutual interdependence? He also noted that the film borrows concepts from other religions and compared its Tree of Souls with the Norse story of the tree Yggdrasil, also called axis mundi or the center of the world, whose destruction signals the collapse of the universe.[83] Malinda Liu in Newsweek likened the Na'vi respect for life and belief in reincarnation with Tibetan religious beliefs and practices,[67] but Reihan Salam of Forbes called the species "perhaps the most sanctimonious humanoids ever portrayed on film."[27]A Bolivian writer defined "avatar" as "something born without human intervention, without intercourse, without sin", comparing it to the birth of Jesus Christ, Krishna, Manco Capac, and Mama Ocllo and drew parallels between the deity Eywa of Pandora and the goddess Pachamama worshiped by the indigenous people of the Andes.[10] Another suggested that the world of Pandora mirrored the Garden of Eden.[84] A writer for Religion Dispatches countered that Avatar "begs, borrows, and steals from a variety of longstanding human stories, puts them through the grinder, and comes up with something new."[85] Another commentator called Avatar "a new version of the Garden of Eden syndrome" pointing to what she viewed as phonetic and conceptual similarities of the film's terminology with that of the Book of Genesis.[86]

Parallels with Hinduism

Cameron calls the connection a "subconscious" reference: "I have just loved ... the mythology, the entire Hindu pantheon, seems so rich and vivid." He continued, "I didn't want to reference the Hindu religion so closely, but the subconscious association was interesting, and I hope I haven't offended anyone in doing so."[13] He has stated that he was familiar with a lot of beliefs of the Hindu religion and found it "quite fascinating".[64]

Answering a question from Time magazine in 2007, "What is an Avatar anyway?" James Cameron replied, "It's an incarnation of one of the Hindu gods taking a flesh form. In this film what that means is that the human technology in the future is capable of injecting a human's intelligence into a remotely located body, a biological body."[89] In 2010, Cameron confirmed the meaning of the title to the Times of India: "Of course, that was the significance in the film, although the characters are not divine beings. But the idea was that they take flesh in another body."[64]

Following the film's release, reviewers focused on Cameron's choice of the religious Sanskrit term for the film's title. A reviewer in the Irish Times traced the term to the ten incarnations of Vishnu.[59] Another writer for The Hindu concluded that by using the "loaded Sanskrit word" Cameron indicated the possibility that an encounter with an emotionally superior—but technologically inferior—form of alien may in the future become a next step in human evolution—provided we will learn to integrate and change, rather than conquer and destroy.[90]

Maxim Osipov of ISKCON argued in The Sydney Morning Herald that "Avatar" is a "downright misnomer" for the film because "the movie reverses the very concept [that] the term 'avatar'—literally, in Sanskrit, 'descent'—is based on. So much for a descending 'avatar', Jake becomes a refugee among the aborigines."[48] Vern Barnet in Charlotte Observer likewise thought that the title insults traditional Hindu usage of the term since it is a human, not a god, who descends in the film.[83] However, Rishi Bhutada, Houston coordinator of the Hindu American Foundation, stated that while there are certain sacred terms that would offend Hindus if used improperly, 'avatar' is not one of them.[88] Texas-based filmmaker Ashok Rao added that 'avatar' does not always mean a representative of God on Earth, but simply one being in another form—especially in literature, moviemaking, poetry and other forms of art.[88]

Explaining the choice of the color blue for the Na'vi, Cameron said "I just like blue. It's a good color ... plus, there's a connection to the Hindu deities, which I like conceptually."[12] Commentators agreed that the blue skin of the Na'vi, described in a New Yorker article as "Vishnu-blue",[91] "instantly and metaphorically" relates the film's protagonist to such avatars of Vishnu as Rama and Krishna.[59][92] An article in the San Francisco Examiner described an 18th-century Indian painting of Vishnu and his consort Laksmi riding the great mythical bird Garuda as "Avatar prequel" due to its resemblance with the film's scene in which the hero's blue-skinned avatar flies a gigantic raptor.[93] Asra Q. Nomani of The Daily Beast likened the hero and his Na'vi mate Neytiri to images of Shiva and Durga.[94]

Critics saw an "undeniably" Hindu connection between the film's story and the Vedic teaching of reverence for the whole universe, as well as the yogic practice of inhabiting a distant body by one’s consciousness[59] and compared the film's love scene to tantric practices.[94] Another linked the Na'vi earth goddess Eywa to the concept of Brahman as the ground of being described in Vedanta and Upanishads and likened the Na'vi ability to connect to Eywa with the realization of Atman.[95] One commentator noted the parallel between the Na'vi greeting "I see you" and the ancient Hindu greeting "Namaste", which signifies perceiving and adoring the divinity within others.[96] Others commented on Avatar's adaptation of the Hindu teaching of reincarnation,[97][98]—a concept, which another author felt was more accurately applicable to ordinary human beings that are "a step or two away from exotic animals" than to deities.[30]

Writing for the Ukrainian Day newspaper, Maxim Chaikovsky drew detailed analogies between Avatar's plot and elements of the ancient Bhagavata Purana narrative of Krishna, including the heroine Radha, the Vraja tribe and their habitat the Vrindavana forest, the hovering Govardhan mountain, and the mystical rock chintamani.[99][100] He also opined that this resemblance may account for "Avatar blues"—a sense of loss experienced by members of the audience at the conclusion of the film.[100][101]

Pantheism vs. Christianity

Some Christian writers worried that Avatar promotes pantheism and nature worship. A critic for L’Osservatore Romano of the Holy See wrote that the film "shows a spiritualism linked to the worship of nature, a fashionable pantheism in which creator and creation are mixed up."[9][102] Likewise, Vatican Radio argued that the film "cleverly winks at all those pseudo-doctrines that turn ecology into the religion of the millennium. Nature is no longer a creation to defend, but a divinity to worship."[102] According to Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi, these reviews reflect the Pope's views on neopaganism, or confusing nature and spirituality.[102] On the other hand, disagreeing with the Vatican's characterization of Avatar as pagan, a writer in the National Catholic Reporter urged Christian critics to see the film in the historical context of "Christianity's complicity in the conquest of the Americas" instead.[103]Other Christian critics wrote that Avatar has "an abhorrent New Age, pagan, anti-capitalist worldview that promotes goddess worship and the destruction of the human race"[32][106] and suggested that Christian viewers interpret the film as a reminder of Jesus Christ as "the True Avatar".[10][107] Some of them also suspected Avatar of subversive retelling of the biblical Exodus, by which Cameron "invites us to look at the Bible from the side of Canaanites."[108] Conversely, other commentators concluded that the film promotes theism[84] or panentheism[95] rather than pantheism, arguing that the hero "does not pray to a tree, but through a tree to the deity whom he addresses personally" and, unlike in pantheism, "the film's deity does indeed—contrary to the native wisdom of the Na'vi—interfere in human affairs."[84] Ann Marlowe of Forbes agreed, saying that "though Avatar has been charged with "pantheism", its mythos is just as deeply Christian."[36] Another author suggested that the film's message "leads to a renewed reverence for the natural world—a very Christian teaching."[95] Saritha Prabhu, an Indian-born columnist for The Tennessean, saw the film as a misportrayal of pantheism: "What pantheism is, at least, to me: a silent, spiritual awe when looking (as Einstein said) at the 'beauty and sublimity of the universe', and seeing the divine manifested in different aspects of nature. What pantheism isn't: a touchy-feely, kumbaya vibe as is often depicted. No wonder many Americans are turned off." Prabhu also criticized Hollywood and Western media for what she saw as their generally poor job of portraying Eastern spirituality.[20]

References

- ^ "Avatar (2009)—Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ "Avatar". The-Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c "James Cameron, Director". charlierose.com. February 17, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Keating, Joshua (January 17, 2010). "Avatar: an all-purpose allegory". Foreign Policy. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Simpson, Jake (January 26, 2010). "Colonialism, Capitalism, Racism: 6 Avatar 'Isms'". The Atlantic Wire. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (January 10, 2010). "Why is 'Avatar' a film of 'Titanic' proportions?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Boehm, Mike (February 23, 2010). "The politics of 'Avatar:'The moral question James Cameron missed". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c Ordoña, Michael (December 14, 2009). "Eye-popping 'Avatar' pioneers new technology". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Itzkoff, Dave (January 20, 2010). "You saw what in ‘Avatar’? Pass those glasses!". New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Huascar Vega Ledo (January 7, 2010). "Jesus Christ and the movie Avatar". BolPress via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Desjardins, Pierre (January 28, 2010). "Avatar: Nothing but a 'stupid justification for war!'". Le Monde via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Svetkey, Benjamin (January 15, 2010). "'Avatar:' 11 burning questions". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Jamkhandikar, Shilpa (March 15, 2010). ""Avatar" may be subconsciously linked to India – Cameron". Reuters India. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Douthat, Ross (December 21, 2009). "Heaven and Nature". New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ Atkins, Dennis (January 7, 2010). "Conservative criticism of Avatar is misplaced". The Courier Mail. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Monbiot, George (January 11, 2010). "Mawkish, maybe. But Avatar is a profound, insightful, important film". Guardian. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Gross, Terry (February 18, 2010). "James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination". National Public Radio. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Cohen, Adam (December 25, 2009). "Next-generation 3-D medium of 'Avatar' underscores its message". The New York Times. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ a b "Evo Morales praises Avatar". ABI. Huffington Post. January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Prabhu, Saritha (January 22, 2010). "Movie storyline echoes historical record". The Tennessean. Archived from the original on January 31, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Brooks, David (January 7, 2010). "The Messiah complex". New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Romm, Joseph (March 7, 2010). "Post-Apocalypse now". ClimateProgress.org. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Salaheldin, Dalia (January 21, 2010). "I see you...". IslamOnline. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ "Day in pictures". SFGate. Associated Press. February 12, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "Palestinians dressed as the Na'vi from the film Avatar stage a protest against Israel's separation barrier". The Daily Telegraph. February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Assi, Seraj (February 17, 2010). "Watching 'Avatar' from Palestinian perspective". Arab News. Archived from the original on 2011-12-30. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c Salam, Reihan (December 21, 2009). "The case against 'Avatar'". Forbes. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Lang, Brent (January 13, 2010). "James Cameron: Yes, 'Avatar' is political". thewrap.com. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "'Avatar' lost at Oscars due to perceived anti-U.S. theme: Cameron". Zee News. March 16, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Marowitz, Charles (March 8, 2010). "James Cameron's Avatar. Film Review". Swans magazine. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ a b Hoyle, Ben (December 11, 2009). "War on Terror backdrop to James Cameron's Avatar". The Australian (News Limited). Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Hamaker, Christian (December 18, 2009). "Otherworldly 'Avatar' familiar in the worst way". Crosswalk.com. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Panyushkin, Valery (February 12, 2010). "Я—один из мерзавцев" [I am one of the scoundrels]. Vedomosti (in Russian). Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ Panyushkin, Valery (January 30, 2010). [I am one of the scoundrels]

|trans-title=requires|title=(help). Vedomosti via translation by WorldMeets.US. Retrieved March 8, 2010. - ^ a b c White, Armond (December 15, 2009). "Blue in the face". New York Press. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Marlowe, Ann (December 23, 2009). "The most neo-con movie ever made". Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Khan, Huma (January, 2010). "The politics of 'Avatar:' conservatives attack film's political message". ABC News. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Beck, Glenn (March 8, 2010). "Glenn Beck: Oscar buzz (zzz)". www.glennbeck.com. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Russell D. (December 21, 2009). "Avatar: Rambo in reverse". The Christian Post.

- ^ a b Podhoretz, John (December 28, 2009). "Avatarocious". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Nolte, John (December 11, 2009). "Review: Cameron’s ‘Avatar’ is a big, dull, America-hating, PC revenge fantasy". bighollywood.breitbart.com. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Mudede, Charles (January 4, 2010). "The globalization of Avatar". The Stranger (newspaper) Slog. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Schlussel, Debbie (December 17, 2009). "Don’t believe the hype: "Avatar" stinks (long, boring, unoriginal, uber-left)". Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Murphy, Mekado (December 21, 2009). "A few questions for James Cameron". The Carpetbagger blog of The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Ditzian, Eric; Horowitz, Josh (February 18, 2010). "James Cameron responds to right-wing 'Avatar' critics". mtv.com. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Adams, Sam (December 22, 2009). "Going Na'vi: Why Avatar's politics are more revolutionary than its images". The A.V. Club.

- ^ a b Osipov, Maxim (December 27, 2009). "What on Pandora does culture or civilisation stand for?". Hindustan Times. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c Osipov, Maxim (January 4, 2010). "Avatar’s reversal of fortune". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Fine, Jeffrey (March 12, 2010). "Why Avatar didn't win the Oscar: Psychologist Dr. Jeffrey Fine asserts the corporate world is bulldozing America". The Miami Herald. PRNewswire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Matos, Altino (January 9, 2010). "Avatar holds out hope for something better". Journal de Angola via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Quinn, David (January 29, 2010). "Spirituality is real reason behind Avatar's success". Irish Independent. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Washington, Jesse (January 11, 2010). "'Avatar' critics see racist theme". Associated Press. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (December 18, 2009). "When will white people stop making movies like "Avatar"?". io9. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Mardell, Mark (January 3, 2010). "Is blue the new black? Why some people think Avatar is racist". BBC. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ "Avatar 2009". goodnewsfilmreviews.com. December 20, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (January 1, 2010). "Avatar recycles indigenous 'stereotypes'". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ Joffe, Josef (January 17, 2010). "Avatar: A shameful example of Western cultural imperialism". Die Zeit. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj (March 4, 2010). "Return of the natives". New Statesman. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Rajsekar, Priya (March 9, 2010). "An Irishwoman's diary". Irish Times. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Brackman, Harold (December 30, 2009). "About avatars: Caveat emptor!". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Linde, Harold (January 4, 2010). "Is Avatar radical environmental propaganda?". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Kirkland, Bruce (April 21, 2010). "Earth Day ‘Avatar’ sends message". QMI Agency. Toronto Sun. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Hibbs, Thomas S. (April 22, 2010). "'Avatar' on Earth Day". National Review Online. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Porie, Koel (March 20, 2010). "SRK means India for Cameron". The Times of India. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Oscar van den Boogaard. "What does avatar mean to you?". De Standaard via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Pottinger, Lori (January 21, 2010). "Avatar: Should Brazil ban the film?". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c Liu, Milinda (February 4, 2010). "Confucius says: Ouch—'Avatar' trumps China's great sage". Newsweek. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Schmidt, Diane J. (February 17, 2010). "Avatar unmasked: the real Na'vi and unobtanium". pej.org. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Nolte, John (March 6, 2010). "James Cameron declares thoroughly debunked global warming as severe a threat as WWII". bighollywood.breitbart.com. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Ben Block, Alex (March 24, 2010). "James Cameron trashes Glenn Beck". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ "10 questions for James Cameron". Time magazine. March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Thottam, Jyoti (February 13, 2010). "Echoes of Avatar: Is a tribe in India the real-life Na'vi?". Time magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Hopkins, Kathryn (February 8, 2010). "Indian tribe appeals for Avatar director's help to stop Vedanta". The Guardian. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Husser, Amy (March 5, 2010). "Environmentalists say Avatar's oilsands allegory deserves Oscar". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Lowe, David (March 6, 2010). "Tribe's fight to save their Pandora". The Sun. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian firms upset with oilsands-slamming ad in Variety". Edmonton Journal. March 4, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved October 12 7, 2010.

- ^ Fischetti, Peter (March 6, 2010). "'Avatar' director wins different award from Temecula-area environmentalists". The Press-Enterprise (California). Archived from the original on 2010-08-06. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Boaz, David (January 26, 2010). "The right has Avatar wrong". Cato Institute. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ This criticism was suspected as a factor in the government's pulling the film from Chinese 2D theaters early in January 2010. Zhou, Raymond (January 8, 2010). "Twisting Avatar to fit China's paradigm". China Daily via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Avatar's story should frighten city developers". Global Times. January 7, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-08-06. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Editorial (January 22, 2010). "Krylatskiy townspeople treated like Avatar natives". Vedomosti (Russia). worldmeet.us. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Goldberg, Jonah (December 30, 2009). "Avatar and the faith instinct". National Review Online. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Barnet, Vern (January 16, 2010). "'Avatar' upends many religious suppositions". Charlotte Observer. p. 4E. Archived from the original on February 15, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Milliner, Matthew (January 12, 2010). "Avatar and its conservative critics". thepublicdiscourse.com. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Plate, S. Brent (January 28, 2010). "Something borrowed, something blue: Avatar and the myth of originality". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Himsel, Angela (February 19, 2010). "Avatar meets Garden of Eden". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Kazmi, Nikhat (December 17, 2009). "Avatar". The Times of India. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c Lassin, Arlene (December 29, 2009). "New movie Avatar shines light on Hindu word". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 13, 2010. Unknown parameter

|middle=ignored (help) - ^ Winters Keegan, Rebecca (January 11, 2007). "Q&A with James Cameron". Time magazine. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Nayar, Parvathi (December 24, 2009). "Encounters of the weird kind". The Hindu. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (October 26, 2009). "Man of extremes: The return of James Cameron". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Wadhwani, Sita (December 24, 2009). "The religious backdrop to James Cameron's 'Avatar'". CNN Mumbai. Cable News Network Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Gereben, Janos (February 15, 2009). "Avatar, the prequel, at the Asian Art Museum". San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on 2010-04-13. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Nomani, Asra Q. (March 5, 2010). "The tantric sex in Avatar". The Daily Beast. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Tam (January 16, 2010). "'Avatar', blue skin and the ground of being". NoozHawk. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Shayon, Sheila (March 15, 2010). "Avatar in us all". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ French, Zenaida B. (March 1, 2010). "Two critiques: ‘Avatar’ vis-à-vis 'Cinema Paradiso'". The News Today Online. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Mattingley, Terry (March 3, 2010). "A spiritual year at the multiplex". East Valley Tribune. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Chaikovsky, Maxim (February 12, 2010). "О Сократе, байдарках и синей тоске" [On Socrates, kayaks, and Avatar blues]. Den (newspaper) (in Russian). Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Chaikovsky, Maxim (February 12, 2010). "Avatar: James Cameron's ode to Lord Krishna". Den (newspaper) via translation by worldmeets.us. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Piazza, Jo (January 11, 2010). "Audiences experience 'Avatar' blues". CNN. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Vatican critical of Avatar's spiritual message". CBC News. January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Martinez, Dimentria (January 20, 2010). "Criticism of 'Avatar' spiritualism off base". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Outten, David (December 15, 2009). "Capitalism, Christianity and Avatar". movieguide.org. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Outten, David (January 29, 2010). "Avatar wins Golden Globe: Cameron pushes pantheism on TV". movieguide.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ "Avatar: Get rid of human beings now!". movieguide.org. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-04-13. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Lane (December 23, 2009). "The true Avatar". The Christian Post. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Pui-Lan, Kwok (January 10, 2010). "Avatar: A subversive reading of the Bible?". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Jeffrey (2010). Spiritual Teachings of the Avatar: Ancient Wisdom for a New World. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster (Atria Books). ISBN 978-1-58270-281-0

- Mahoney, Kevin Patrick (2010). Carmine, Alex, ed. The Ultimate Fan's Guide to Avatar, James Cameron's Epic Movie (Unauthorized). London, UK: Punked Books. ISBN 978-0-9533172-5-7

External links

| ||||||||||||||

13] Christians, including the Vatican, worried that the film promotes pantheism over Christian beliefs, while others instead thought that it sympathetically explores biblical concepts. Other critics either praised the film's spiritual elements or found them hackneyed.[14]

ReplyDeleteThose Christians shouldn't worry about the film 'promoting' pantheism over Christian beliefs. I don't think it 'sympathetically' explores biblical concepts which are all false to me. Biblical concepts are false and some are immoral including the support of slavery and stoning of disobedient kids. If the film promoted pantheism over Christian beliefs that would be okay as some people are pantheists and that is okay. Why should filmmakers kiss the asses of intolerant Christians. Some people don't agree with Christian beliefs including pantheists.

The Vatican is wrong for making an issue of the film 'promoting' pantheism. Even if the film promoted pantheism that would be okay. It's not like you have to convert to pantheism. Some people are pantheists and they have the right to hold pantheistic beliefs. The Vatican should be ashamed over their bigotry towards pantheism.

ReplyDeletei heard about this blog & get actually whatever i was finding. Nice post love to read this blog

ReplyDeleteGST consultant In Indore

digital marketing consultant In Indore

This article discusses the importance of this blog for business promotion. Promoting a blog is just like promoting any other website and can be difficult to do if you are not sure what needs to be done, but with the right tips and Buy yahoo accounts tricks, this doesn't have to be. Hopefully, you find this article on this blog helpful and decide to visit the site below to see just what they are talking about.

ReplyDeleteThis is an awesome blog post. The author has used images that show an object in the sky as clouds. When I first looked at the image it did not look like a cloud, but it looked like a cloud. So the title of this post is This is Awesome Blog Post.

ReplyDeleteproperty for rent in abu dhabi with photos